Event-Driven Gameplay in ExcaliburJS

A Primer on Excalibur Event Emitters

Intro

As your game grows, so does the complexity of its logic.

Enemies need to react to the player. Animations need to trigger damage. AI systems need to coordinate state changes. UI needs to update when something happens — but that “something” might come from anywhere.

One approach is direct calls:

ts

ts

This works… until it doesn’t.

Suddenly everything knows about everything else. A small change in one system ripples through your entire codebase. Reuse becomes difficult. Debugging becomes painful.

This is where event-driven architecture shines — and ExcaliburJS provides a powerful, flexible event system that can be used as a tool to connect different systems.

In this article, we’ll explore:

- What Excalibur’s event framework actually gives you

- Why publish/subscribe (pub/sub) patterns matter in games

- Practical, real-world use cases

- And how to model gameplay events, not just callbacks

Events are a tool. Any tool can help you solve a specific set of problems. As with any other tool, if you start applying this solution to the wrong problems, there are potential foot-guns. We will discuss this a bit.

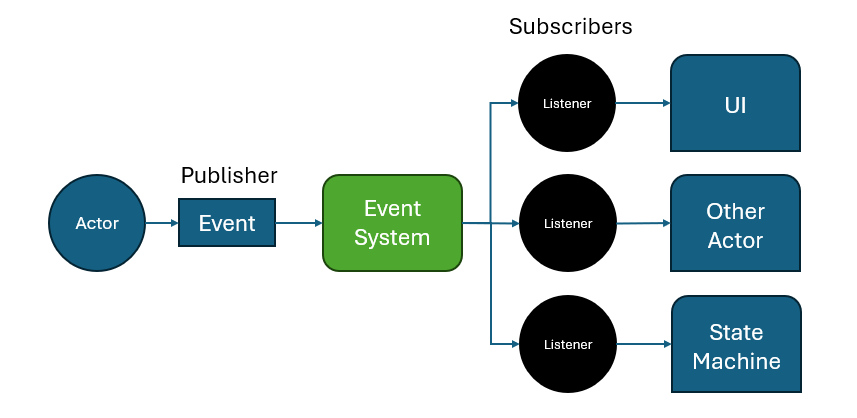

What Is Pub/Sub (and Why It Fits Games So Well)

At its core, Excalibur’s event system follows a publish/subscribe model:

- One system emits an event

- Zero or more systems listen for it

- The publisher has no knowledge of who’s listening — or if anyone is at all

This decoupling is incredibly valuable in games, where many systems often react to the same stimulus.

Benefits of Pub/Sub in Game Architecture

-

Loose Coupling

Your listening systems don't need to know about the emitter. For example: Your UI doesn’t need to know about combat math. They just react to events.

-

Semantic Meaning

Events turn low-level mechanics into high-level intent:

"collisionstart" → "enemySpotted""frame" → "attackHit"hp <= 0" → "died" -

Fan-Out by Default

One event can trigger:

- Sound

- Visual effects

- State changes

- Analytics

…without a single direct dependency.

-

Easier Iteration

Want to add screen shake on hit? Just listen to an event — no refactors required.

Events in ExcaliburJS (A Quick Mental Model)

Almost everything in Excalibur has an .events property:

- Actor

- Scene

- Engine

- Animation

And you can:

- Listen with .on(...)

- Remove with .off(...)

- Emit with .emit(...)

- Create your own typed event emitters

This makes Excalibur events ideal for gameplay signaling, not just engine hooks. The two HUGE benefits with using the emitter is built-in type safety and leverage native IDE tools like Intellisense with autocomplete. This is a big quality of life feature.

The Three Pillars of ExcaliburJS Events

Excalibur’s event system is deceptively simple on the surface — but when used properly with TypeScript, it becomes a strongly-typed, scalable messaging system.

Everything builds on three pillars:

- Event type definitions

- Extending GameEvents

- Const declaration event maps

Once you understand how these fit together, you can confidently model almost any gameplay interaction.

1. Event Type Definitions

At the most basic level, Excalibur events are just named signals with payloads. We can use an event interface to map the semantic event names to the actual GameEvents that are emitted.

ts

ts

This event map answers two questions:

- What events can be emitted?

- Which events are mapped?

2. Extending GameEvents

Then you define the specific events and their payloads.

ts

ts

3. Const Declaration (optional, but improves DevX)

Declaring the events 'as const' provices replacing magic strings with enum-like behaviors.

ts

ts

The events are ready to use!

Using the events

Here's how to use these as extensions of Actor events (one way to use them)

ts

ts

Passing parameters in the event

When you call the .emit() method, the 2nd parameter you pass is what shows up as the incoming parameter for the event listener.

For example:

ts

ts

Common Gameplay Use Cases for Events

Here are some use cases and game dev patterns where Excalibur’s event system really shines:

- Perception systems (vision, hearing, proximity)

- AI state transitions

- Combat pipelines (chaining attacks!!!)

- Animation timing

- UI synchronization

- Cross-entity communication (enemy alarms!!!)

- Designer-friendly extensibility

Let’s walk through three concrete examples.

Use Case 1: Line-of-Sight as an Actor Component

Line-of-sight detection is a perfect example of continuous logic that should emit discrete events.

Instead of asking every frame: “Can I see the player?”

We want:

- "targetSeen"

- "targetLost"

The Pattern: Line-of-Sight Component

Instead of baking events directly into the Actor, we can encapsulate behavior in a component:

The LineOfSightComponent handles math, raycasts, and visibility checks.

It emits semantic events like seen or lost.

Other systems (AI, UI, audio) can respond without knowing the implementation details.

Define your component

ts

ts

Use Case 2: Finite State Machines via Events

State machines often start simple — and quickly become tangled.

ts

ts

Now multiply that across:

- Combat

- Damage

- Stuns

- Animations

- Death

Event-Driven FSMs

Instead of polling conditions, let events drive transitions:

ts

ts

The FSM:

- Doesn’t know about physics

- Doesn’t know about raycasts

- Only reacts to meaningful signals

This pattern scales exceptionally well games that have scaled in size.

Use Case 3: Child Actors as Sensors (Extending Actor Events)

Excalibur Actors already emit collision events — but sometimes you want specialized detection zones.

Instead of overloading the main actor:

- Add a child actor

- Give it its own collider

- Translate physics events into gameplay events

We will quickly revisit the example given earlier, focusing on how to combine the events with the Native Actor emittor.

ts

ts

This demonstrates two powerful ideas:

- Extending actor behavior without inheritance

- Using child actors as modular sensors

It’s especially effective for:

- Stealth games

- Traps

- Trigger zones

- Area-based AI awareness

Footguns and Pitfalls

To be objective in this info, let's call out where a pub/sub system can go wrong.

When Not to Use Pub/Sub (and Why)

Event-driven architecture is powerful — but it’s not free.

Just because Excalibur makes events easy doesn’t mean everything should be an event. Overusing pub/sub can introduce subtle bugs, obscure control flow, and make your game harder to reason about.

Here are the most common drawbacks — and how to recognize when pub/sub is the wrong tool.

1. Hidden Control Flow

Events obscure sequence of operations, you don't have exact control over when and what order things happen.

If you have direct callbacks, you are in complete control of execution, with events, you hand that off to the event system. You can lose traceabilty of who all is listening to the event, and in what specific order the events are reacted to.

You no longer know:

- Who is listening

- In what order handlers run

- What side effects will occur

This can make debugging harder — especially when behavior changes “magically.” Events like this are 'one-way' so if you need some acknowledgement from a receiver, then an event is probably not the best design choice.

2. Debugging Can Become Non-Local

An event emitted in one file may trigger behavior across different systems and components:

- Actors

- Components

- Scenes

- UI

- Audio systems

This can make tracking down something that breaks more complicated.

3. Overcomplicating simple tasks

If you are connecting two elements, an event bus may be overkill and add unnecessary comlexity.

When Events are the right tool

Use events when:

- Multiple systems may react

- You’re translating engine mechanics into gameplay meaning

- You want extensibility without refactors

- You’re modeling state changes, not actions

Avoid events when:

- Order is critical

- Only one system will ever care

- The caller needs a return value

- The logic is simple and local

Summary

In this article, we explored the ExcaliburJS events feature.

We started by explaining the fundamentals of pub/sub systems and breaking down the three pillars of Excalibur’s event system. From there, we applied those ideas to an ECS component, using a LineOfSightComponent as a concrete example, tying events to triggering a Finite State Machine, and extending the native Actor events that already exist.

This is where Excalibur’s event model shines.

It’s not a global pub/sub free-for-all. It’s a scoped, typed messaging system that encourages:

- Local reasoning

- Explicit contracts

- Testable gameplay units

- Scalable architecture as projects grow

Events work best when they represent meaningful state transitions, not every frame-by-frame detail. When used this way, they become natural boundaries between systems — and those boundaries are what keep game code flexible, understandable, and fun to work in.

Why ExcaliburJS

Small plug for the engine that makes this all possible:

ExcaliburJS is a friendly, TypeScript 2D game engine for the web. It's free and open source (FOSS), well documented, and has a growing community of developers building great games.

Excalibur event emitters are just one example of how Excalibur's architecture makes complex features feel natural. If you're interested in 2D web game development, check it out!

Join the Discord community for questions and support.